A Road Map to Clean Water, Jobs and Justice:

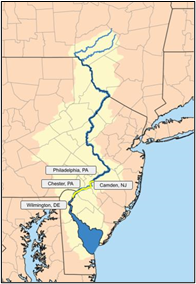

In the “Missing Section” of the Delaware RiveR

The William Penn Foundation is providing support for a study to identify water quality improvement opportunities to reduce bacteria in the 27 mile stretch of the Delaware River flowing past Philadelphia, Camden, Chester and Wilmington. Working with people representing all aspects of the River’s use, the goal is to develop a “Road Map” to increase equitable opportunities for swimming and paddling in targeted areas as well as advance community health, public access, and job creation.

The Delaware River is one of the most important and scenic rivers in the United States, providing the drinking water to 15 million people. Thankfully, its water quality has dramatically improved due to the combination of action taken by governments, utilities, businesses and citizens. This improvement was celebrated when American Rivers named the Delaware River its National River of the Year for 2020.

HOWEVER, a stark example of inequity stands out when one learns that today all 330 miles of the Delaware River have water quality that is acceptable for “primary contact recreation” use except for the 27 mile stretch of the Delaware River that runs past the Cities of Philadelphia, Camden, Chester, and Wilmington.

For more information about this project, please contact R[email protected]

The Delaware River is one of the most important and scenic rivers in the United States, providing the drinking water to 15 million people. Thankfully, its water quality has dramatically improved due to the combination of action taken by governments, utilities, businesses and citizens. This improvement was celebrated when American Rivers named the Delaware River its National River of the Year for 2020.

HOWEVER, a stark example of inequity stands out when one learns that today all 330 miles of the Delaware River have water quality that is acceptable for “primary contact recreation” use except for the 27 mile stretch of the Delaware River that runs past the Cities of Philadelphia, Camden, Chester, and Wilmington.

For more information about this project, please contact R[email protected]

The residents of these four cities, each with significant minority populations and with median household incomes of under $50,000, must live adjacent to the only section of the entire Delaware River with inadequate water quality.

Each of these cities has combined sewer systems (systems in which the stormwater and sanitary sewers are combined into one pipe) which were undersized when built and thereby unable to convey or treat all of the combined sewage flow that is generated when it rains. As a result, in the 27-mile stretch from Philadelphia to Wilmington, combined sewage can back up into basements of homes, streets, and parks, or can overflow into the Delaware River and its tributaries.

It is difficult to imagine a starker picture of social injustice than children walking through puddles of sewage to get to their bus stops, or sewage backing up into basements when it rains. HOWEVER, the situation where the residents of Philadelphia, Camden, Chester, and Wilmington live along a River where they cannot safely swim, paddle or wade, because of combined sewage overflows, is a prime example of an environmental injustice that can be addressed in the near term.

Each of these cities has combined sewer systems (systems in which the stormwater and sanitary sewers are combined into one pipe) which were undersized when built and thereby unable to convey or treat all of the combined sewage flow that is generated when it rains. As a result, in the 27-mile stretch from Philadelphia to Wilmington, combined sewage can back up into basements of homes, streets, and parks, or can overflow into the Delaware River and its tributaries.

It is difficult to imagine a starker picture of social injustice than children walking through puddles of sewage to get to their bus stops, or sewage backing up into basements when it rains. HOWEVER, the situation where the residents of Philadelphia, Camden, Chester, and Wilmington live along a River where they cannot safely swim, paddle or wade, because of combined sewage overflows, is a prime example of an environmental injustice that can be addressed in the near term.

The study will focus on identification of projects, along with corresponding costs and benefits, which will result in enjoyment and economic potential for “more people, more times, more places”

through the development of a Road Map or path forward to provide cleaner water, less sewage, healthier communities, and better recreational access and use.

As Congress turns its attention to the overwhelming national need for investments in infrastructure, jobs and economic recovery, resulting legislation can provide avenues to address these inequities, providing

immediate opportunity to advance the clean water, jobs and community revitalization outcomes identified in the Road Map.

By reducing combined sewage flooding into homes, streets and parks, investment in these historic cities and environmental justice communities will address longstanding inequities:

through the development of a Road Map or path forward to provide cleaner water, less sewage, healthier communities, and better recreational access and use.

As Congress turns its attention to the overwhelming national need for investments in infrastructure, jobs and economic recovery, resulting legislation can provide avenues to address these inequities, providing

immediate opportunity to advance the clean water, jobs and community revitalization outcomes identified in the Road Map.

By reducing combined sewage flooding into homes, streets and parks, investment in these historic cities and environmental justice communities will address longstanding inequities:

- improving quality of community life and property values;

- providing appropriate water access for recreation and economic benefit;

- sparking economic development with new construction and associated jobs;

- creating climate friendly new green infrastructure to improve communities as well as create entry level jobs and experiences such as Power Corps in Philadelphia and Camden for opportunity youth;

- reducing overall rate burden associated with current City commitments to reduce pollution;

The provision of critically necessary new federal funding, review of current funding mechanisms, assessment of existing priorities, and use of different technology can make a meaningful difference in the quality of life for residents, remove some of the unjust pollution burdens that they face, and spark economic development, job creation and business growth.

The Water Center at the University of Pennsylvania (WCP) is conducting the fact-based analysis.

The American Littoral Society is leading stakeholder engagement to help the WCP share its information with a diverse group of people, representing various interests. It is important that community values and views are part of the project development and evaluation to ensure that the Road Map has the benefit of representative knowledge and experience.

Exciting gains from clean water are starting to become visible across the 27 mile stretch.

Support for water infrastructure funding will reduce and prevent pollution through proven and permanent measures, generating benefits to the residents of the “missing section” of the River.

Residents in Philadelphia, Chester, Camden and Wilmington, regardless of their means, deserve access to clean water near safe public spaces to reflect, recharge, and seek refuge in times of challenge and in times of joy. In the words of a graduate of UrbanPromise, “I want my part of the River to be as nice as the River up north.”

For additional information, please contact [email protected]

Revitalizing Philadelphia’s Rivers and Creeks

Philadelphia has the opportunity to take the “ball down the field” to prepare for climate change, enable equitable and safe access, provide healthier waters, rebuild the waterfronts, create new jobs with skilled work training, and revitalize the city as both a place to live and to visit.

These benefits can be realized through using once-in-a-lifetime federal water pollution, construction, training funding opportunities, and revisions in City financing measures, accompanied by a set of commonsense, time-tested water quality policies. Time is of the essence in rectifying the historical disinvestment in Philadelphia’s sewage pollution problems.

READ MORE

These benefits can be realized through using once-in-a-lifetime federal water pollution, construction, training funding opportunities, and revisions in City financing measures, accompanied by a set of commonsense, time-tested water quality policies. Time is of the essence in rectifying the historical disinvestment in Philadelphia’s sewage pollution problems.

READ MORE

|

The Coalition for the Delaware River Watershed hosted a webinar on Monday, October 5 to share information on a project seeking to promote fair and equitable opportunities to “get more people, more often, in more places” swimming, paddling and enjoying the 27 mile stretch of the Delaware River flowing past Philadelphia, Camden and Chester.

The Water Center, University of Pennsylvania, and the American Littoral Society, with the support of the William Penn Foundation, are creating a “road map” of possible improvements and a process to advise policy makers on preferred paths for relatively short-term action that would result in better water quality in targeted areas of the Delaware River in order to support swimming, wading, and paddling. |

|

Roadmap to Clean Water, Jobs and Justice in the News

A battle brews over use of the Delaware River: Recreational vs. commercial

As environmentalists try to encourage more cleanup — and more recreational use of the river — advocates for commercial interests push back

SUSAN PHILLIPS | MARCH 29, 2022 | ENERGY & ENVIRONMENT, WATER

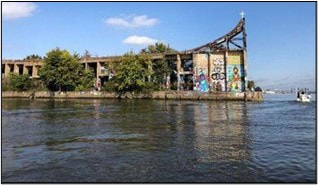

Taking a trip to the banks of the Delaware River on a warm summer day these past couple of years, you may have seen people paddling kayaks, floating on inflatable pink flamingos, racing by on jet skis, and even swimming. It’s a sign that the river, once known as a “stinky ugly mess,” is now much cleaner and more inviting.

It’s also the result of an effort by advocates and environmentalists to encourage more recreational use of the river.

But not everyone is cheering a recreational return to the Delaware. Each year, about 4,000 large cargo ships carry everything from plywood to steel to grapes, delivering material to 30 different marine terminals in the 27-mile stretch between the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge and the Commodore Barry Bridge. Thousands of work boats, including barges and tugs, also travel that stretch each year.

The Maritime Exchange for the Delaware River and Bay, a trade association for the commercial shipping industry that helps manage the traffic, says the increased recreational activities risk fatal collisions with container ships that ply the Delaware. The group is pushing back against efforts to upgrade the river’s regulatory designation under the Clean Water Act.

“Even were the water quality improved, the area would still not be safe for primary contact recreation,” Maritime Exchange president Lisa Himber wrote in a letter to Philadelphia City Council in December.

READ MORE at NJ Spotlight News

Taking a trip to the banks of the Delaware River on a warm summer day these past couple of years, you may have seen people paddling kayaks, floating on inflatable pink flamingos, racing by on jet skis, and even swimming. It’s a sign that the river, once known as a “stinky ugly mess,” is now much cleaner and more inviting.

It’s also the result of an effort by advocates and environmentalists to encourage more recreational use of the river.

But not everyone is cheering a recreational return to the Delaware. Each year, about 4,000 large cargo ships carry everything from plywood to steel to grapes, delivering material to 30 different marine terminals in the 27-mile stretch between the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge and the Commodore Barry Bridge. Thousands of work boats, including barges and tugs, also travel that stretch each year.

The Maritime Exchange for the Delaware River and Bay, a trade association for the commercial shipping industry that helps manage the traffic, says the increased recreational activities risk fatal collisions with container ships that ply the Delaware. The group is pushing back against efforts to upgrade the river’s regulatory designation under the Clean Water Act.

“Even were the water quality improved, the area would still not be safe for primary contact recreation,” Maritime Exchange president Lisa Himber wrote in a letter to Philadelphia City Council in December.

READ MORE at NJ Spotlight News

On rafts, inner tubes and flamingoes, they promote Camden’s river

Advocates use flotilla to press for continued cleanup and better recreational access to Delaware River

BY JON HURDLE, CONTRIBUTING WRITER | NJ SPOTLIGHT | AUGUST 10, 2021 | ENERGY & ENVIRONMENT, WATER

On a warm August afternoon, a ragged raft of plastic flotation devices and other watercraft carrying around 40 people drifted slowly on the tide up a Delaware River channel between the Camden County riverfront and Petty’s Island, site of a former oil terminal.

Saturday’s gathering might have been mistaken for just a bunch of partiers out on the water for a few hours. But this was Floatopia, a rally designed to build support for improved public access to the Delaware River in a community that for generations has shunned the waterway as a recreational asset, and to press for the river’s continued cleanup.

To show their support for a more user-friendly river, participants lolled in the laps of inflatable flamingoes, unicorns and assorted plastic rings tied to kayaks and two floating docks, and steered by two motorized boats that provided some measure of control over the unwieldy flotilla.

Click here to read more

On a warm August afternoon, a ragged raft of plastic flotation devices and other watercraft carrying around 40 people drifted slowly on the tide up a Delaware River channel between the Camden County riverfront and Petty’s Island, site of a former oil terminal.

Saturday’s gathering might have been mistaken for just a bunch of partiers out on the water for a few hours. But this was Floatopia, a rally designed to build support for improved public access to the Delaware River in a community that for generations has shunned the waterway as a recreational asset, and to press for the river’s continued cleanup.

To show their support for a more user-friendly river, participants lolled in the laps of inflatable flamingoes, unicorns and assorted plastic rings tied to kayaks and two floating docks, and steered by two motorized boats that provided some measure of control over the unwieldy flotilla.

Click here to read more

27 miles to go: getting the last piece of the Delaware swimmable and fishable

By Meg McGuire | January 8, 2021

27 miles.

Not that far, really.

About the distance between Philly and Chester.

And in fact, that's exactly the part of the river that we're talking about.

It's the most populous stretch of the river and it's attracting attention from all the people who live along that corridor. These days people are eager to live near it, walk next to it, paddle in it, kayak in it.

Such good news about a river that was once, like 60 years ago, an open sewer that stank to high heaven and nobody had much hope of improving it. A lot has changed in 60 years.

But in this stubborn 27 miles, the river gets really complicated. So it's getting a different sort of attention from a project called "Returning to the River: More People, More Often, More Places."

The idea behind this effort is that sometimes, some stretches of that 27 miles are fine for people to be in it or on it. But sometimes those same stretches can be a problem, largely because of bacteria that cause illnesses in humans; bacteria that get past the various wastewater treatment facilities that dot this section of the river.

Click the following link to read more: https://delawarecurrents.org/2021/01/08/27-miles-to-go-getting-the-last-piece-of-the-delaware-swimmable-and-fishable/

By Meg McGuire | January 8, 2021

27 miles.

Not that far, really.

About the distance between Philly and Chester.

And in fact, that's exactly the part of the river that we're talking about.

It's the most populous stretch of the river and it's attracting attention from all the people who live along that corridor. These days people are eager to live near it, walk next to it, paddle in it, kayak in it.

Such good news about a river that was once, like 60 years ago, an open sewer that stank to high heaven and nobody had much hope of improving it. A lot has changed in 60 years.

But in this stubborn 27 miles, the river gets really complicated. So it's getting a different sort of attention from a project called "Returning to the River: More People, More Often, More Places."

The idea behind this effort is that sometimes, some stretches of that 27 miles are fine for people to be in it or on it. But sometimes those same stretches can be a problem, largely because of bacteria that cause illnesses in humans; bacteria that get past the various wastewater treatment facilities that dot this section of the river.

Click the following link to read more: https://delawarecurrents.org/2021/01/08/27-miles-to-go-getting-the-last-piece-of-the-delaware-swimmable-and-fishable/

DELAWARE RIVER POLLUTION SHOULD BE A NATIONAL CONCERN

Call for clean water, justice and jobs in environmental justice communities like Camden, Chester, Philadelphia and Wilmington

BY TIM DILLINGHAM, ANDREW KRICUN, DON BAUGH | MAY 11, 2021

Perhaps nowhere in the nation are the issues of environmental, social and economic inequities and injustice more evident than in a 27-mile stretch of the Delaware River valley bordered by the cities of Camden, Chester, Philadelphia and Wilmington.

Our country faces a series of challenges that have exposed long-standing vulnerabilities to the health of our environment, our communities and our democracy. In addition, the American Society of Civil Engineers recently graded our nation’s drinking water infrastructure a C- and its wastewater infrastructure a D+, which represents entirely inadequate protection of the public health and the environment.

And, unfortunately, a significantly disproportionate burden of this infrastructure inadequacy directly impacts environmental justice communities such as Camden, Chester, Philadelphia and Wilmington. We believe very strongly that everyone, regardless of where they live and what they look like, is entitled to safe drinking water and clean waterways. Yet, the 27-mile stretch of the Delaware River that flows past these cities is the only section of this 300-mile river not designated for direct water contact by government agencies. This is caused by chronic overflows from antiquated combined sewer systems which — during normal rain events — can push raw sewage into the streets, homes, parks and neighborhoods of these environmental justice cities, as well into the river. This is not only a public health and environmental problem, but also a social justice problem. No one, no matter where they live or what they look like, should have to worry about their basement backing up with sewage when it rains, or their children walking through puddles of sewage to get to their bus stops.

The Biden administration and Congress are currently developing a national infrastructure spending plan. It is on the order of billions, if not trillions, of dollars to be invested in finally upgrading our crumbling national infrastructure, mostly discussing roads, bridges and energy. The funding package must also consider and provide dollars for clean water, justice and jobs in overburdened communities — and several do. Federal investment in cleaning up the pollution of the Delaware River adjacent to Philadelphia, Chester, Wilmington and Camden should be a high and immediate priority. Such an investment, long overdue, can bring equitable improvements in the quality of life, remove some of the unjust pollution burdens facing riverfront communities, and spark economic development, jobs and business creation.

A National Investment

A national investment is needed as these communities cannot, and should not have to, bear the costs of the needed improvements alone. These communities deserve to be able to enjoy the same quality of life as everyone else, without having to bear crippling rate increases. The adjacent Delaware River — an economic powerhouse for most communities — provides only promises of economic development and quality-of-life enhancement that others in different ZIP codes enjoy. Strong and innovative local leadership has demonstrated how addressing these problems, through green infrastructure parks in Camden and Philadelphia’s visionary “Green City, Clean Water” program, could work. These exemplary efforts need to be expanded, accelerated and implemented; doing so will improve community landscapes, provide jobs and bring the promise of the Delaware River to life. This vision cannot be achieved through local ratepayers alone. It is a model example of where the Biden administration and Congress should partner and direct the developing infrastructure funding program.

We are at a moment in history where we might truly achieve clean water, justice and jobs in addressing the water pollution burdens on our communities, supporting them in growth, jobs and improvements in community life. Local leaders need to call for attention and funding for these problems, direct some of the immediately available American Rescue Plan Act funding to ready projects and work with national leaders to build a strong and sustained commitment to cleaning up a significantly overburdened stretch of the Delaware River, America’s founding river.

Tim Dillingham

Tim Dillingham is the executive director of the American Littoral Society

Andrew Kricun

Andrew Kricun is a member of the New Jersey Environmental Justice Advisory Council, and serves as chair of its water committee

Don Baugh

Don Baugh is President of the Upstream Alliance

Perhaps nowhere in the nation are the issues of environmental, social and economic inequities and injustice more evident than in a 27-mile stretch of the Delaware River valley bordered by the cities of Camden, Chester, Philadelphia and Wilmington.

Our country faces a series of challenges that have exposed long-standing vulnerabilities to the health of our environment, our communities and our democracy. In addition, the American Society of Civil Engineers recently graded our nation’s drinking water infrastructure a C- and its wastewater infrastructure a D+, which represents entirely inadequate protection of the public health and the environment.

And, unfortunately, a significantly disproportionate burden of this infrastructure inadequacy directly impacts environmental justice communities such as Camden, Chester, Philadelphia and Wilmington. We believe very strongly that everyone, regardless of where they live and what they look like, is entitled to safe drinking water and clean waterways. Yet, the 27-mile stretch of the Delaware River that flows past these cities is the only section of this 300-mile river not designated for direct water contact by government agencies. This is caused by chronic overflows from antiquated combined sewer systems which — during normal rain events — can push raw sewage into the streets, homes, parks and neighborhoods of these environmental justice cities, as well into the river. This is not only a public health and environmental problem, but also a social justice problem. No one, no matter where they live or what they look like, should have to worry about their basement backing up with sewage when it rains, or their children walking through puddles of sewage to get to their bus stops.

The Biden administration and Congress are currently developing a national infrastructure spending plan. It is on the order of billions, if not trillions, of dollars to be invested in finally upgrading our crumbling national infrastructure, mostly discussing roads, bridges and energy. The funding package must also consider and provide dollars for clean water, justice and jobs in overburdened communities — and several do. Federal investment in cleaning up the pollution of the Delaware River adjacent to Philadelphia, Chester, Wilmington and Camden should be a high and immediate priority. Such an investment, long overdue, can bring equitable improvements in the quality of life, remove some of the unjust pollution burdens facing riverfront communities, and spark economic development, jobs and business creation.

A National Investment

A national investment is needed as these communities cannot, and should not have to, bear the costs of the needed improvements alone. These communities deserve to be able to enjoy the same quality of life as everyone else, without having to bear crippling rate increases. The adjacent Delaware River — an economic powerhouse for most communities — provides only promises of economic development and quality-of-life enhancement that others in different ZIP codes enjoy. Strong and innovative local leadership has demonstrated how addressing these problems, through green infrastructure parks in Camden and Philadelphia’s visionary “Green City, Clean Water” program, could work. These exemplary efforts need to be expanded, accelerated and implemented; doing so will improve community landscapes, provide jobs and bring the promise of the Delaware River to life. This vision cannot be achieved through local ratepayers alone. It is a model example of where the Biden administration and Congress should partner and direct the developing infrastructure funding program.

We are at a moment in history where we might truly achieve clean water, justice and jobs in addressing the water pollution burdens on our communities, supporting them in growth, jobs and improvements in community life. Local leaders need to call for attention and funding for these problems, direct some of the immediately available American Rescue Plan Act funding to ready projects and work with national leaders to build a strong and sustained commitment to cleaning up a significantly overburdened stretch of the Delaware River, America’s founding river.

Tim Dillingham

Tim Dillingham is the executive director of the American Littoral Society

Andrew Kricun

Andrew Kricun is a member of the New Jersey Environmental Justice Advisory Council, and serves as chair of its water committee

Don Baugh

Don Baugh is President of the Upstream Alliance