|

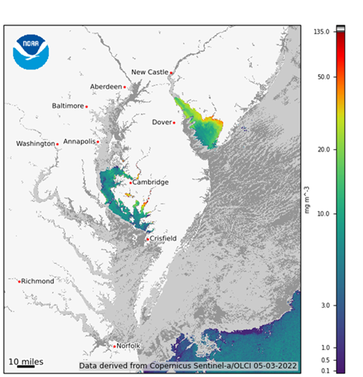

What do you think of when you think of the Littoral Society? Maybe you think about tagging horseshoe crabs on the Delaware Bay, building a living shoreline in the Barnegat Bay, or advocating for public beach access with our team at Sandy Hook. Our mission is to care for the coast and those are some of the most visible ways we do that. So, it’s no wonder that people are often surprised when they find out we also work on stormwater management in upstream cities like Bridgeton and Camden. While it might seem minor, stormwater — that’s water that can’t be absorbed into the ground when it rains due to changes that humans have made to the landscape — has a major impact on the coast. Take it from the fourth-generation oyster farmer, Barney Hollinger, who talks in the video below about how sediment carried by stormwater smothers and chokes his reefs. Clarification: Sometimes we get so excited about protecting our streams and rivers from polluted runoff that we get ahead of ourselves. Lucia around the 4-minute mark mentions that bacteria eats up oxygen levels in waterways. This is because when the algae die, they are decomposed by bacteria—this process consumes the oxygen dissolved in the water and needed by fish and other aquatic life to "breathe".  The map shows chlorophyll concentrations in the Delaware and Chesapeake bays, which can be used to indicate risk of harmful algae looms. Graphic from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. The map shows chlorophyll concentrations in the Delaware and Chesapeake bays, which can be used to indicate risk of harmful algae looms. Graphic from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. When water can’t percolate or seep into the ground, it “runs off” into the nearest river or stream. Even when it flows into a storm drain, that water is often piped directly into the nearest body of water, carrying whatever contaminants it picked up along the way. Unlike under normal circumstances, where water would slowly travel underground, it rushes through the streams at a higher rate, ripping and eroding away the sides of stream banks. In addition to the sediment carried, the sudden influx of freshwater can be deadly to oysters, who need salty water to survive. Then there’s excessive nutrients, one of the biggest pollutants that stormwater carries to the bay. As water travels over land, it picks up animal waste and fertilizers, both of which are full of nitrogen and phosphorus. Once this reaches the bay, normally occurring algae has a free buffet. The algae feasts and multiplies, blocking out the sunlight that underwater vegetation relies on to survive. The enrichment of the waters is known as eutrophication. When the algae completes its life cycle, it's the bacteria’s time to dine. As the bacteria decomposes the algae, it consumes the oxygen in the water. This, combined with vegetation loss, results in a major drop in dissolved oxygen. To help prevent and fight these issues, the Littoral Society advocates for better stormwater management at the state and local level. We also use nature-based solutions, like rain gardens and bioswales, to trap and filter stormwater back into the ground. The results are starting to show, as we’re beginning to see a glimmer of a downtrend in phosphorus in the tributaries to the Delaware Bay. Meanwhile, Barney’s oysters are as delicious as ever. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|